Building a New Family-Level Model: Why Generalization Matters

Published on: December 2025

Goal

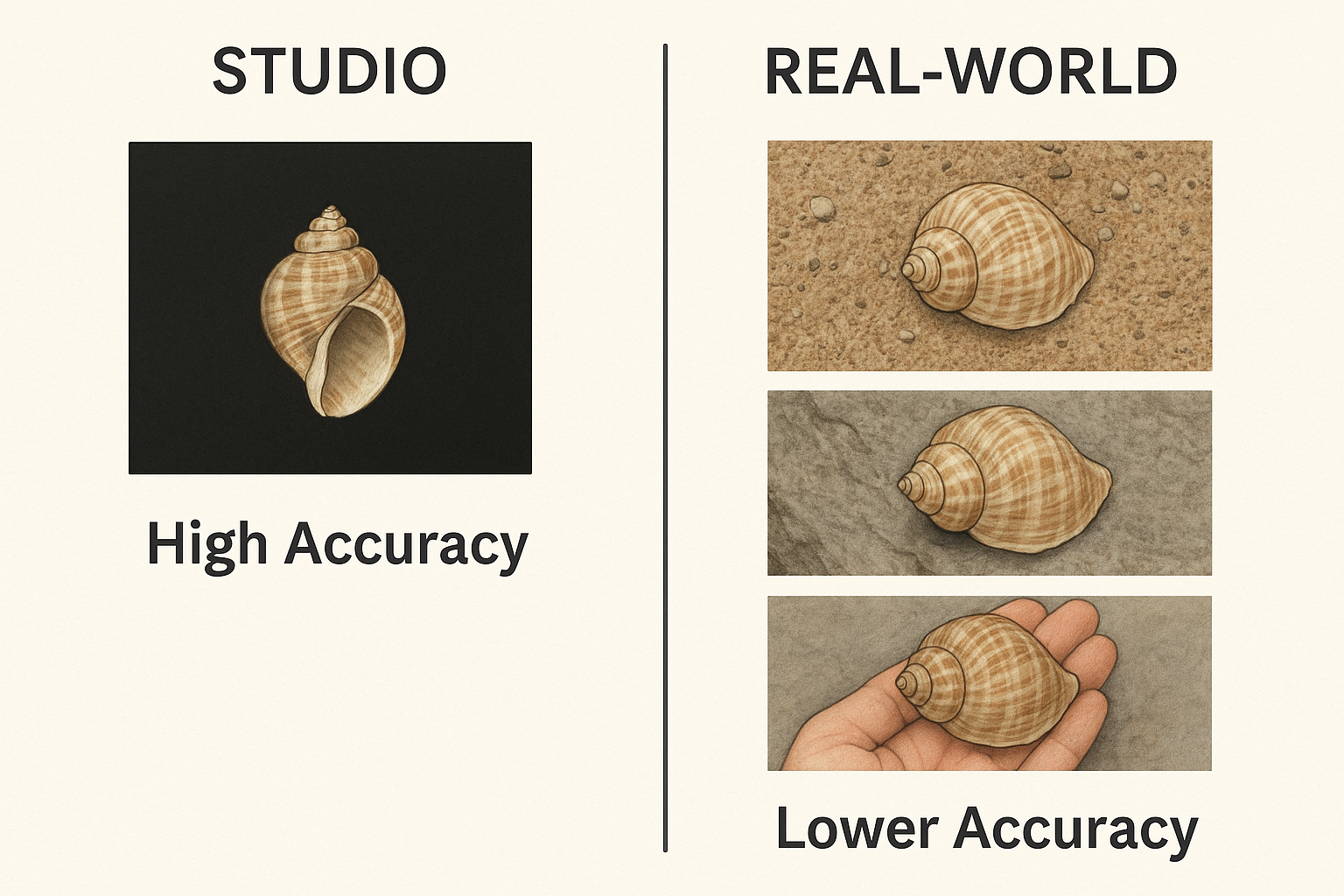

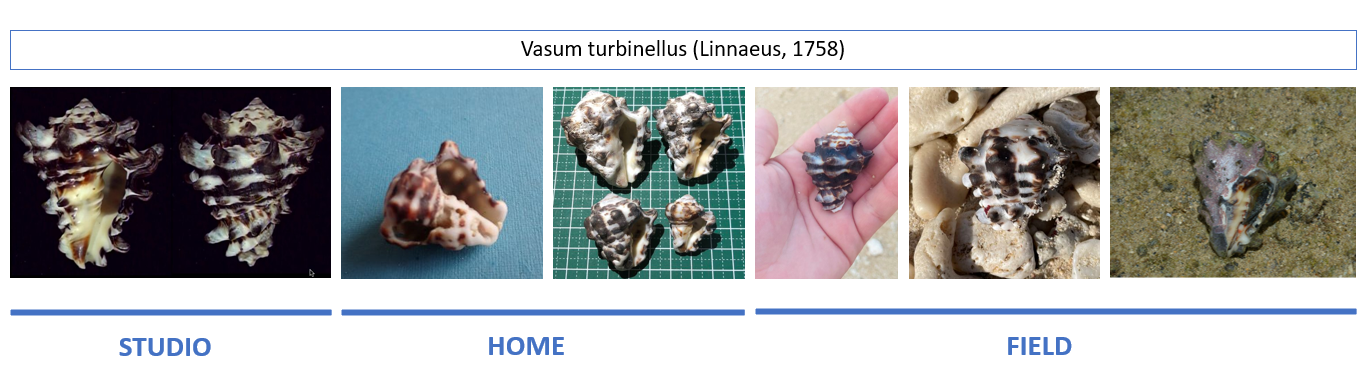

In an earlier post on this blog, an improved phylum-level model used in IdentifyShell was described [1] and it was shown that it performs very well on shell images taken under standardized, controlled conditions. When shells are photographed in the usual viewpoint—aperture facing up or down, centred in the frame, and placed on a clean black background—the original model classifies them reliably. This “studio style” is common in museum collections, specialized dealers and online reference portals, and it formed the majority of the training material. Under those controlled circumstances, the early model was entirely adequate and performed with high accuracy.

The limitation only became visible once users of the IdentifyShell app began submitting their own photographs for identification. These images naturally reflect real-world conditions: they are taken at home, in amateur collections, or directly in the field, often with mobile phones and without any standardized viewpoint or background. Shells appear on sand, rocks, tables, hands, or marine substrate; they may be illuminated by natural light, photographed at odd angles, or partially embedded in their surroundings. As these images entered the system, it became clear that the original model struggled to maintain accuracy. It still recognized many shells but its performance dropped noticeably whenever an image deviated from the studio-like appearance it had learned during training.

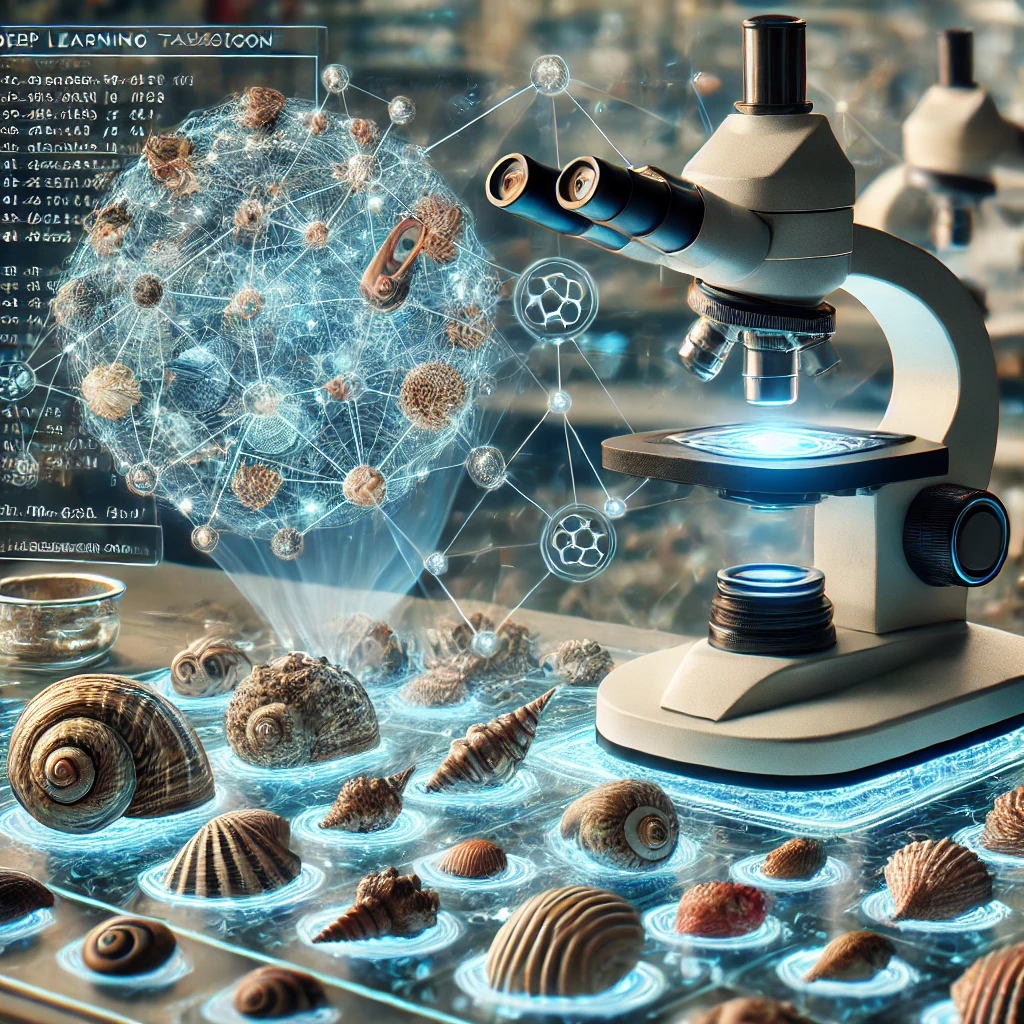

This behaviour reflects a well-known issue in machine learning: the generalization problem. A model may perform extremely well on the type of data it was trained on yet degrade significantly on data drawn from a different “domain.” Neural networks tend to absorb not only the true object features but also the characteristic patterns of the training images — including lighting, background, composition, and viewpoint [2, 3]. For IdentifyShell.org, the model learned to expect a centred shell on a clean black background with controlled lighting. When those expectations were violated, the accuracy of the predictions declined.

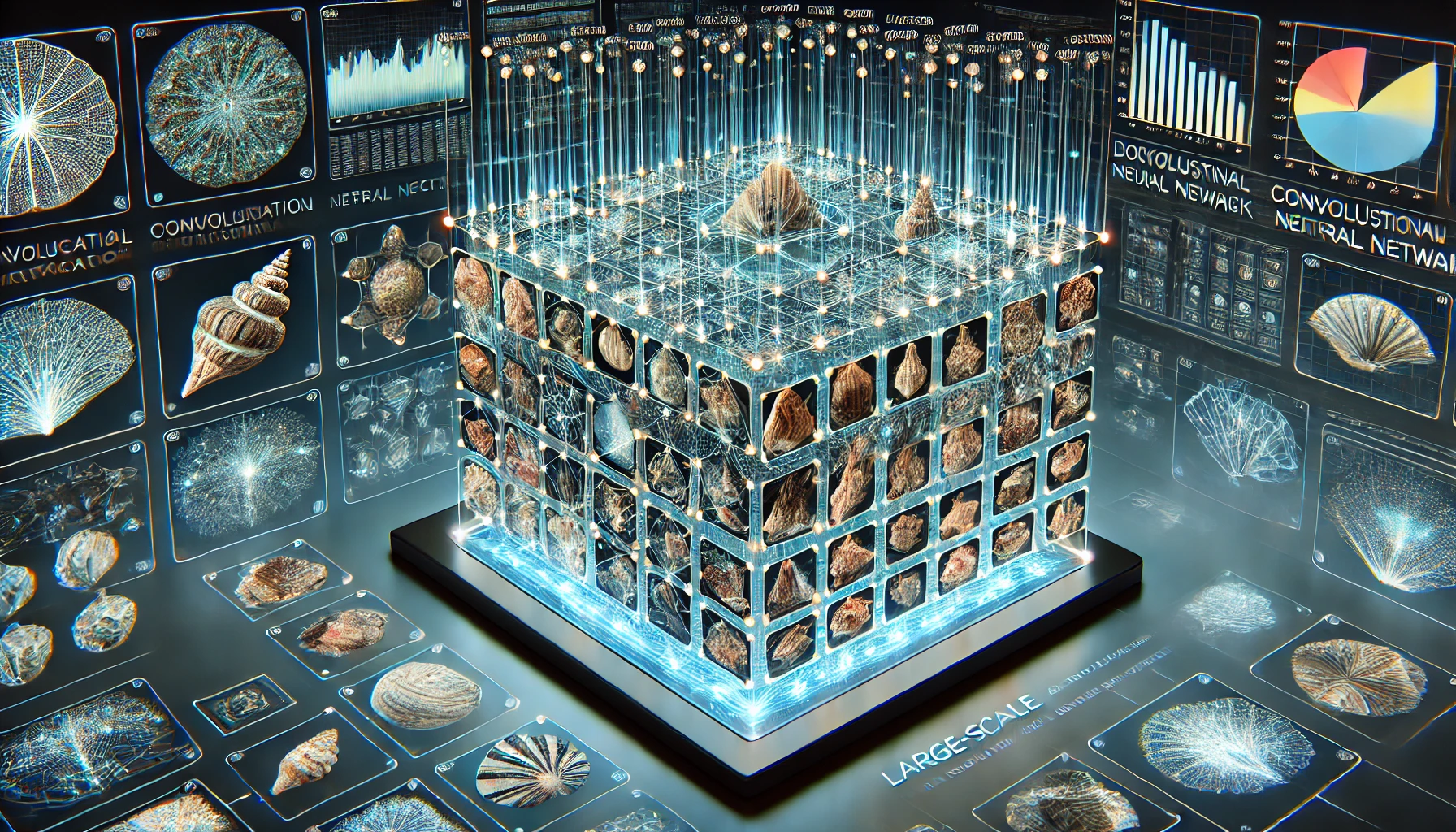

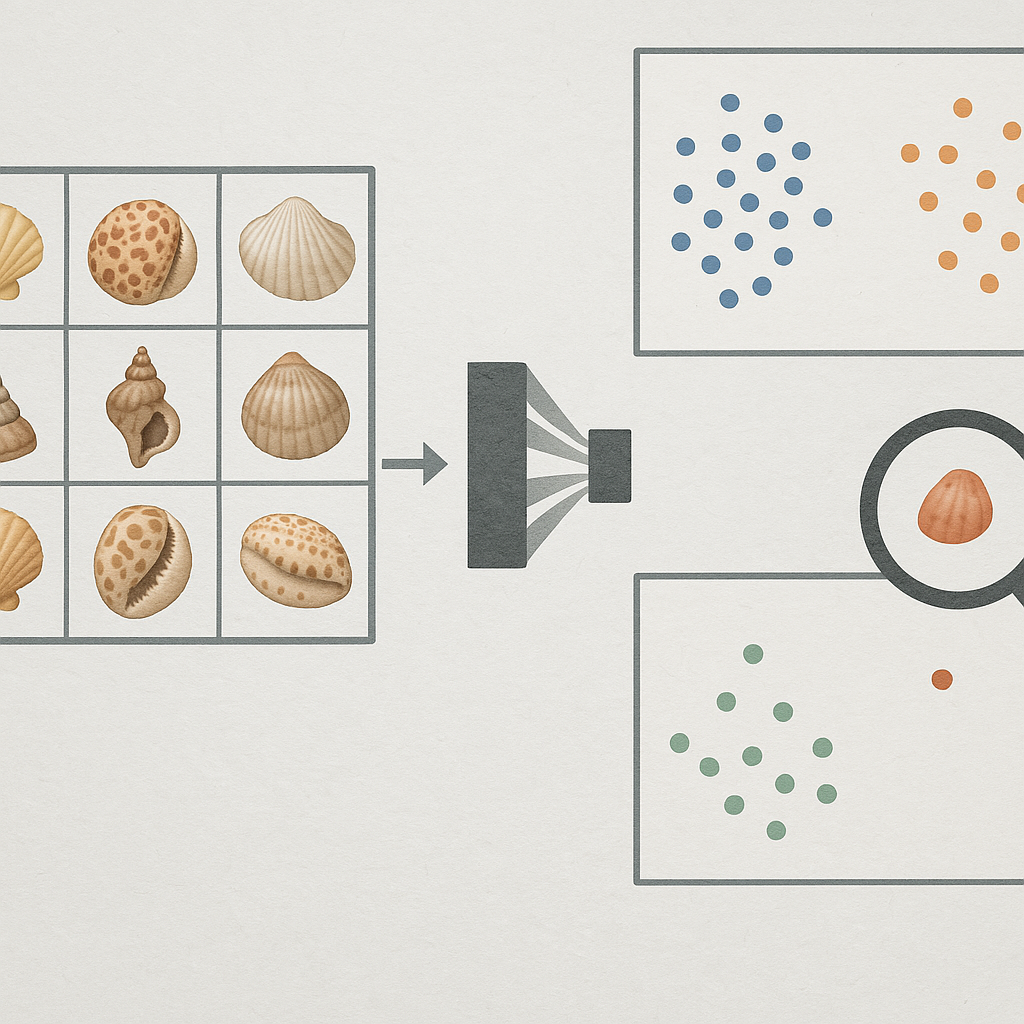

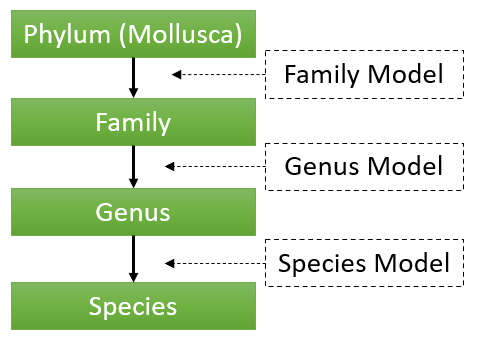

This is particularly important because IdentifyShell.org uses a hierarchical classification system [4]. The pipeline begins with a coarse-grained model that predicts the family. Only after the family has been determined does the system proceed to the genus-level classifier, and finally to a fine-grained species-level model. If the family-level prediction is wrong, all subsequent steps will also be wrong, regardless of how accurate the genus or species models might be. Ensuring robust and domain-invariant predictions at the family stage is therefore essential for the entire hierarchy.

Although family-level classification is coarser than genus or species recognition, it still depends on morphological cues that can be obscured or distorted in non-studio images. Features that separate families—such as the outline of the shell, the relative proportions of the spire and aperture, the presence or absence of certain sculptural elements—may not be visible when the shell is rotated, held in a hand, photographed under uneven lighting, or embedded in habitat material. This sensitivity to viewpoint, background and context is widely documented in fine-grained and mid-grained visual recognition [5, 6] and explains why the original model, despite being accurate under controlled conditions, struggled in real-world use.

It is important to emphasize that the original IdentifyShell model was not incorrect; it was simply over-specialized. It learned to perform well within a very specific visual domain because that was what the training data represented. Once confronted with the full diversity of user-generated images, its limitations became visible. This prompted the need for a new family-level classifier that can generalize across photographic styles, viewpoints and environments.

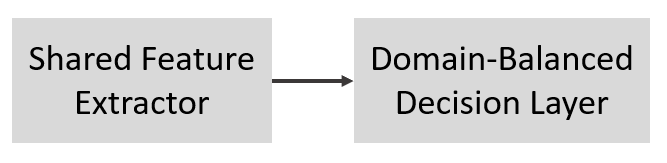

The new model is being designed with this objective at its core. Instead of relying primarily on studio photographs, it draws from multiple domains and uses training strategies intended to promote the extraction of stable morphological features rather than background cues. Stronger augmentation, domain-aware sampling, and active learning are being incorporated so that the network learns to handle the full range of imagery that IdentifyShell users actually submit. By doing so, the system aims to deliver consistent predictions across controlled collection images, home photographs, and challenging field observations alike.

As decades of research in computer vision have shown, achieving good generalization is one of the most difficult problems in deep learning [7, 8, 9]. It does not occur automatically; it must be engineered explicitly. The new IdentifyShell family-level model is built on this principle. It is designed not only to improve accuracy but to ensure that the entire hierarchical pipeline—family, genus, and species prediction—remains reliable when applied to the rich, varied, and inevitably imperfect images produced by real users around the world.

Reports

Toward Universal Shell Classification: Learning Robust Family-Level Representations Across Domains

Convolutional neural networks trained on controlled studio imagery often exhibit strong in-domain performance but degrade substantially when applied to heterogeneous real-world photographs of molluscan shells. This study demonstrates that robust family-level classification under domain shift can be achieved by freezing a high-capacity studio-trained backbone and adapting only the decision boundary using domain-balanced head retraining, resulting in a 13.4 percentage-point gain in field accuracy and a more than 50% reduction in prediction uncertainty. These results show that domain generalization in this setting is primarily a decision-boundary and training-dynamics problem rather than a representational one, establishing a practical baseline for reliable shell identification in unconstrained environments.

Domain-Adaptive Expert Routing with Prototype–Classifier Fusion for Shell Identification (in preparation)

References

- [1] Ph. Kerremans. Optimizing Molluscan CNN Taxonomy: Balancing Hierarchy Simplification, Data Volume, and Augmentation for Improved Classification. IdentifyShell.org (2025).

- [2] A Torralba & A A Efros Unbiased look at dataset bias CVPR, Colorado Springs, CO, USA, pp. 1521-1528 (2011)

- [3] G Wilson & D J Cook A Survey of Unsupervised Deep Domain Adaptation ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST), Volume 11, Issue 5, Pages 1 - 46 (2020)

- [4] Ph. Kerremans. Hierarchical CNN to identify Mollusca. IdentifyShell.org (2025)

- [5] C Wah et al. The Caltech-UCSD Birds-200-2011 Dataset California Institute of Technology (2011)

- [6] N Zang et al. Part-based R-CNNs for Fine-grained Category Detection arXiv:1407.3867 [cs.CV] (2014)

- [7] K. He, X. Zhang, S. Ren and J. Sun Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2016, pp. 770-778 (2016)

- [8] Tan, M., & Le, Q. V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. ICML (2019)

- [9] Chen et al. A Simple Framework for Contrastive Learning of Visual Representations (SimCLR) ICML (2020)