Toward Universal Shell Classification: Learning Robust Family-Level Representations Across Domains

Published on: December 2025

Abstract

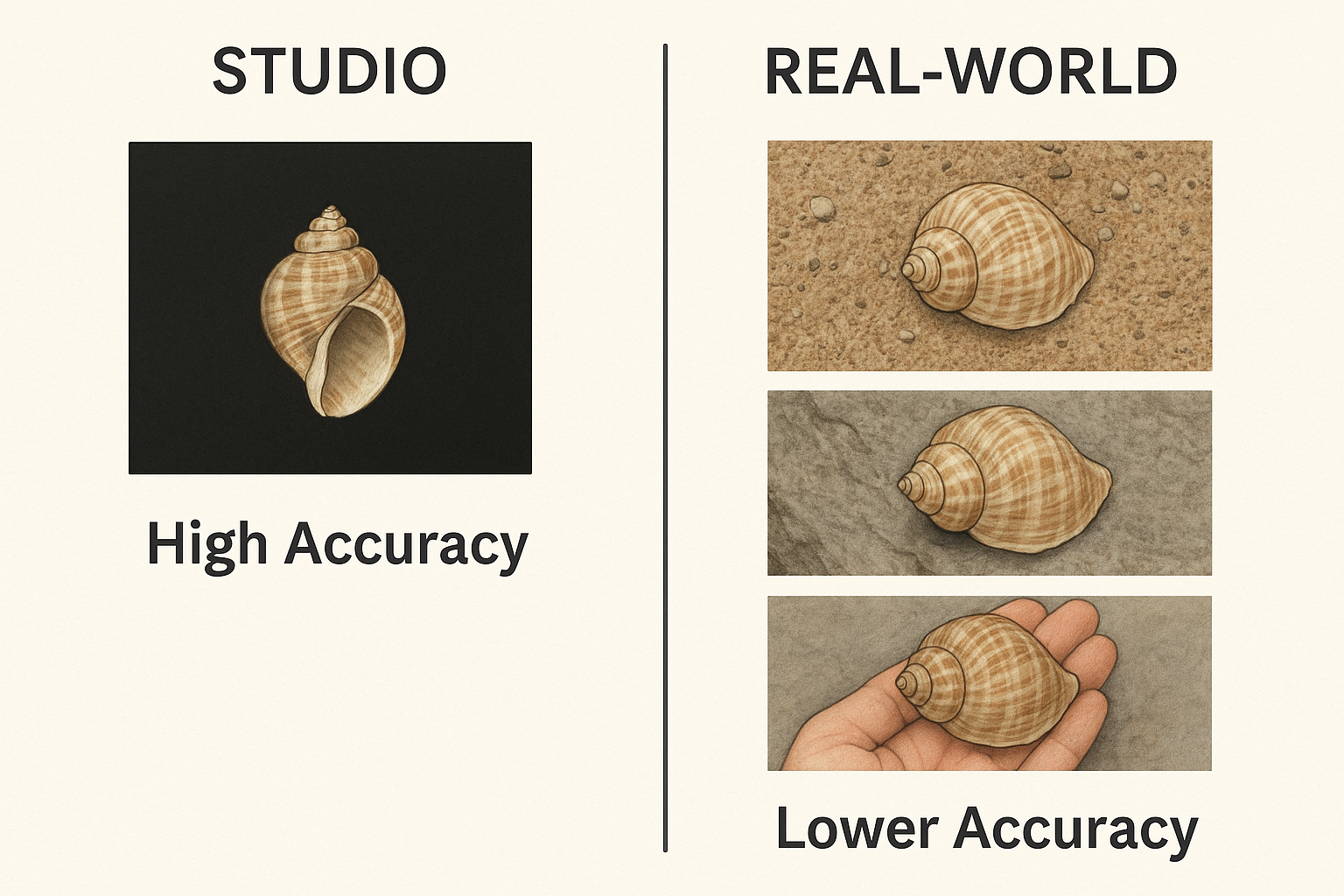

Accurate image-based identification of molluscan shells is a prerequisite for scalable taxonomic workflows, yet models trained under controlled imaging conditions often fail when deployed on photographs captured in unconstrained real-world environments. This work investigates domain generalization at the family level for Mollusca, focusing on the transition from studio-quality images to heterogeneous home and field photographs. Starting from a high-capacity EfficientNetV2-B2 backbone trained on more than 600,000 studio images spanning 90 families, domain robustness is addressed without retraining the feature extractor. Instead, the backbone is frozen and a new classification head is trained using a domain-balanced curriculum that prioritizes field images, combined with cosine normalization, MixUp augmentation, and label smoothing.

Results show that this strategy substantially improves real-world performance, yielding a +13.4 percentage-point gain in field accuracy relative to a studio-only baseline, while incurring a modest −4.9 percentage-point reduction on the source domain. Crucially, the approach reduces global log loss by more than 50%, indicating a marked improvement in probability calibration and prediction reliability under domain shift. These findings demonstrate that the apparent robustness of studio-trained classifiers can be partially illusory, reflecting over-reliance on acquisition-specific cues, and that domain generalization in this setting is primarily a decision-boundary and training-dynamics problem rather than a representational one.

By decoupling feature learning from decision-boundary adaptation and treating domain imbalance explicitly during optimization, this study establishes a practical and reproducible baseline for robust family-level shell classification. The resulting model remains compatible with hierarchical taxonomic pipelines and provides a foundation for future work on domain-aware routing, open-set recognition, and morphology-centric species delimitation.

Introduction

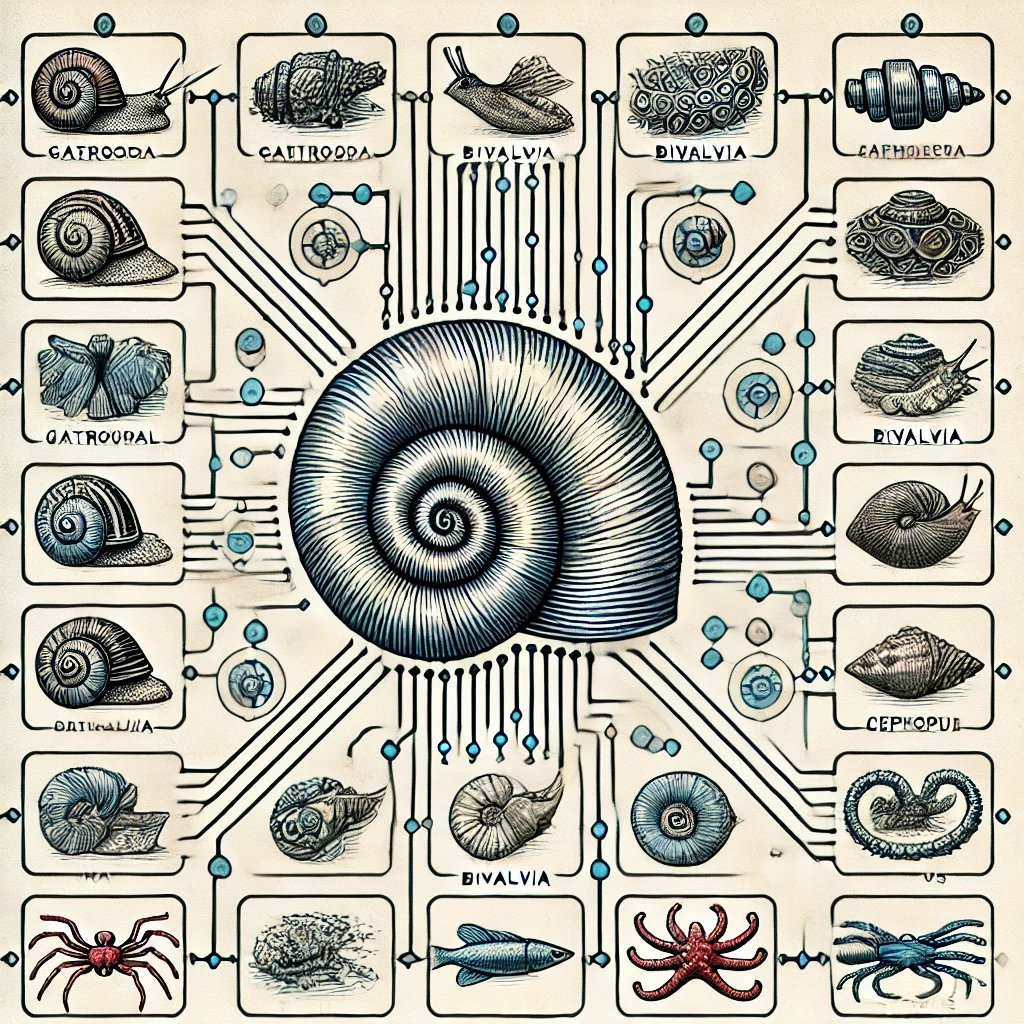

Accurate image‐based identification of molluscan shells underpins a wide range of taxonomic, ecological, and citizen-science applications, but remains difficult because of the enormous morphological diversity within Mollusca and the variability of real-world photographs [1, 2, 3]. Deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have recently enabled large-scale visual taxonomy, including end-to-end pipelines that identify shells from the phylum level down to individual species [4]. In earlier work a hierarchical CNN framework for Mollusca was introduced: separate CNNs are trained for successive taxonomic ranks (phylum, family, genus, species), and predictions are propagated top-down, which improves interpretability and allows each node to be optimized for the morphological structure and data balance of its subset of taxa [5]. Within this hierarchy, the first step is a Mollusca-level model that assigns images to families, providing the entry point for all downstream genus- and species-level classifiers.

In a subsequent study we replaced the original two-stage phylum→order→family cascade with a single “phylum-to-family” classifier based on EfficientNetV2 B2 and trained on more than 600 000 studio-quality shell photographs spanning 90 families [6]. This flat family-level model reduced “order-gate” errors, provided clear guidelines on the number of training images and input resolution required per family, and already showed promising performance on an external test set composed of consumer-grade auction photographs. However, that work still focused on a single, highly controlled source domain: images captured under standardized studio conditions with nearly uniform black backgrounds. As IdentifyShell.org has been deployed to end users, we have observed substantial performance degradation when the same family-level model is confronted with photographs taken at home (non-uniform backgrounds, suboptimal lighting, unusual viewpoints) or in the field at the seashore (complex scenes, variable weather, partial occlusions). These observations fit the broader pattern seen in other computer-vision systems, where accuracy can drop sharply under seemingly mild distribution shifts [7, 8].

This problem can be formalized as a domain generalization task. The studio images constitute the source domain on which the backbone CNN is trained; the home and field photographs represent target domains with different but related data distributions. Domain generalization methods seek models that perform well on such unseen target domains without having access to their data during backbone training [9]. Most existing work has focused on benchmarks like PACS, Office-Home, and the WILDS suite, which highlight that even strong ImageNet-pretrained networks suffer substantial out-of-distribution (OOD) accuracy drops under real-world shifts such as camera traps or geographic regions. Within this literature, our setting is particularly close to single-domain generalization (SDG): the feature extractor is trained on a single high-quality domain and must generalize to multiple unseen domains that differ in style, background, and noise. SDG has been shown to be especially challenging; meta-learning and adversarial augmentation strategies such as M-ADA improve robustness but still leave a sizable gap between in-domain and out-of-domain performance [10].

At the same time, recent transfer-learning and representation-learning results suggest that strong pretrained feature extractors can be remarkably universal when used as frozen backbones with simple linear probes on top. In large-scale studies, ImageNet-pretrained CNNs and modern self-supervised models have been shown to transfer well across diverse tasks when evaluated via frozen features plus a trained classifier head [11]. Moreover, systematic comparisons indicate that full fine-tuning can reduce OOD accuracy relative to linear probing, because updating all weights may distort otherwise good pretrained features [12].

The present work leverages these insights to design and evaluate a domain-generalized family-level classifier for Mollusca. Specifically, the EfficientNetV2 family model trained on studio images was used as a fixed feature extractor and train new classifier heads on labeled examples drawn from three domains: Studio (controlled black-background images), Home (amateur photographs taken indoors or in informal settings), and Field (images taken at or near the seashore). This separation mirrors practical usage: in production, most new images submitted to IdentifyShell originate from home and field settings, yet the bulk of labeled training data remains studio-like. By treating the backbone as frozen and adapting only the family-level head, we can (i) preserve the high-capacity representation learned from hundreds of thousands of curated studio images, (ii) study how different mixtures of domain-specific and domain-agnostic training data in the head affect cross-domain performance, and (iii) keep the resulting model compatible with the existing hierarchical CNN stack used for genus- and species-level classification.

The contributions described are threefold. First, a three-domain benchmark for molluscan shell family classification that reflects real IdentifyShell usage was formalized, with clearly defined Studio, Home, and Field domains aligned with the hierarchical CNN pipeline. Second, building on a frozen EfficientNetV2 backbone trained on studio shells, a linear-probe and shallow-head baselines trained on different domain combinations was evaluated systematically, quantifying how much of the domain gap can be closed without modifying the feature extractor. Third, the resulting cross-domain behavior at the level of individual families was analyzed, highlighting which morphological groups remain brittle under domain shift and providing practical guidelines for curating future training data and designing domain-aware extensions of the hierarchy. Taken together, this study represents the first dedicated investigation of domain generalization for hierarchical molluscan shell classification and provides a reproducible baseline for future methods that seek to bridge the studio-to-field gap in biodiversity image analysis.

Methods

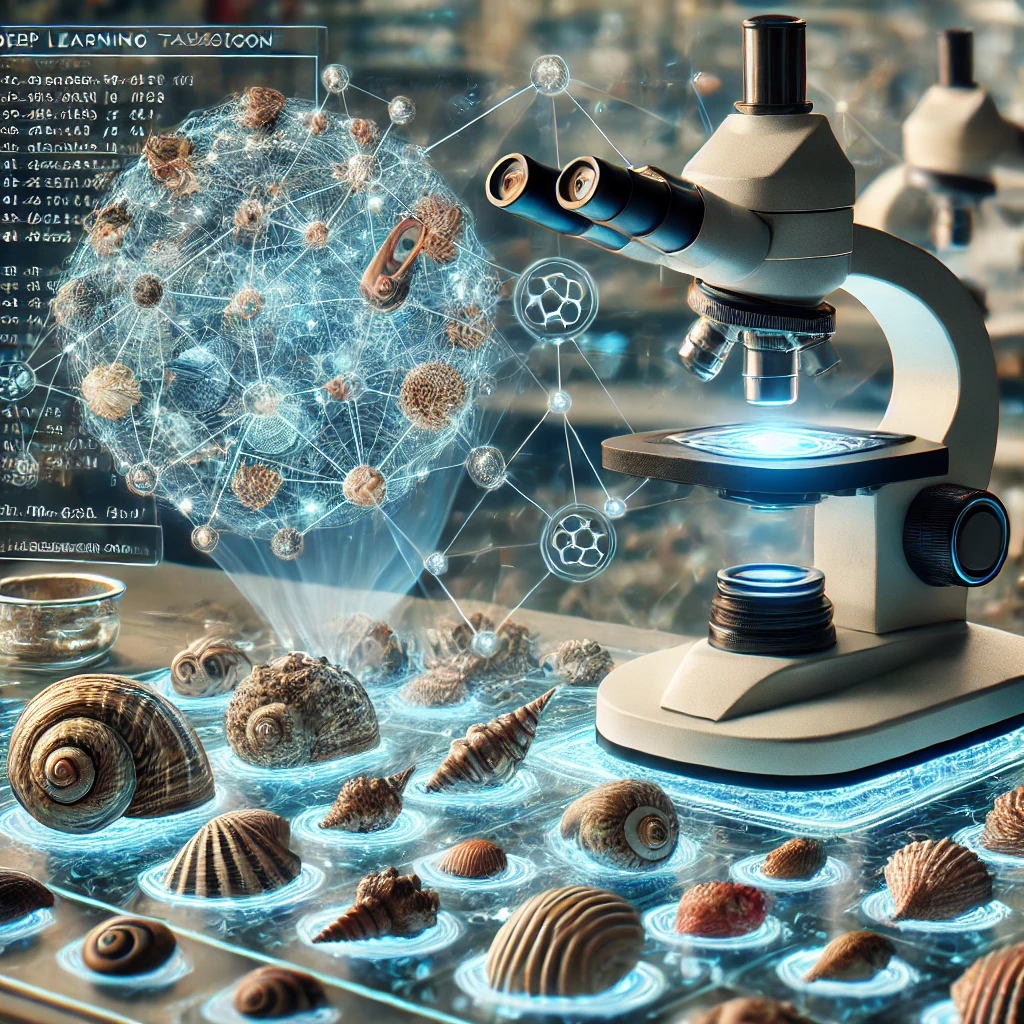

Methodological Framework: Progressive Embedding Construction

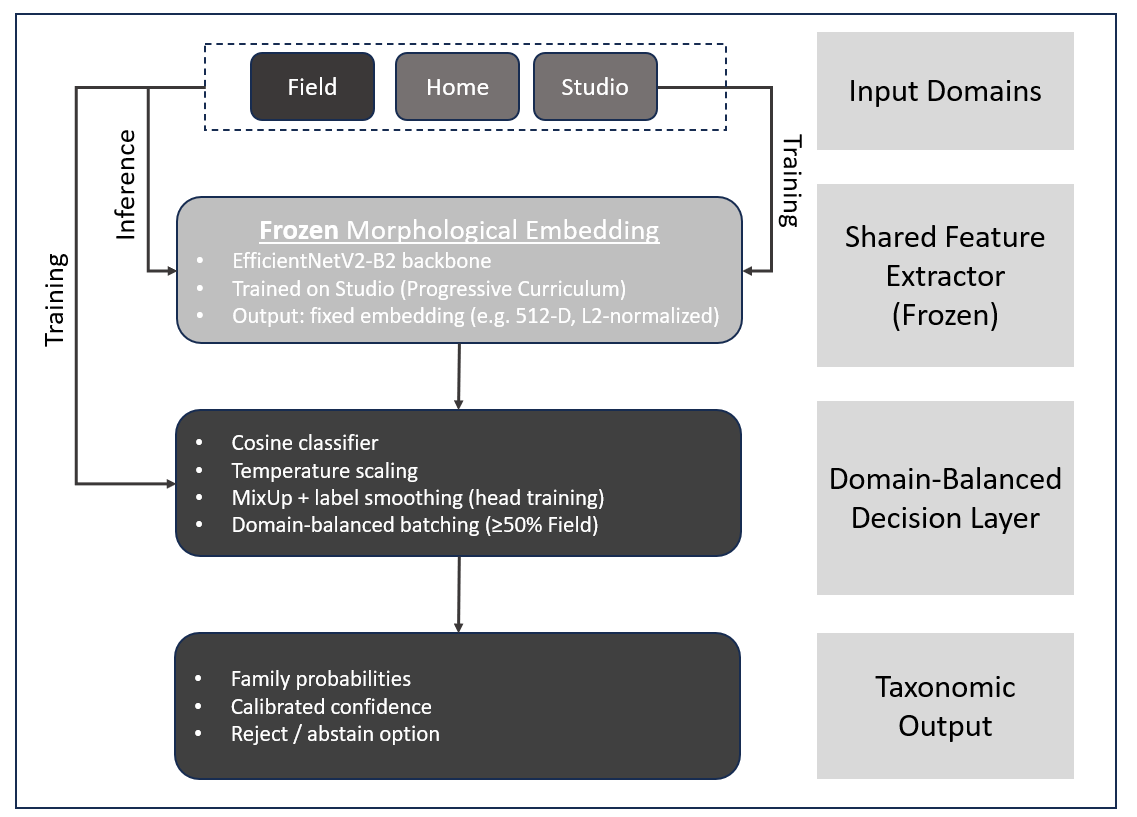

Figure 1. Logical architecture of the domain-generalized family-level classifier.

A shared EfficientNetV2-B2 backbone is trained exclusively on Studio images and then frozen to produce fixed morphological embeddings. Domain

generalization is achieved by retraining a cosine-based family classifier head with domain-balanced batches emphasizing Field images,

yielding calibrated family-level predictions for Studio, Home, and Field inputs.

To develop a feature extractor capable of robust domain generalization, a Progressive Curriculum Learning strategy was employed. Instead of training a monolithic classifier on the entire taxonomic tree simultaneously—which risks overfitting to the long tail of sparse classes — the embedding space was constructed in two distinct phases. This approach allows the network to first stabilize its representation on high-volume taxa ("Head Families") before adapting to a broader morphological scope ("Mid-Tier Families") via rehearsal learning.

Dataset Preparation and Preprocessing

The source domain data consisted of high-resolution, studio-quality RGB photographs of molluscan shells. From the total corpus of approximately 600,000 images, taxonomic families were selected based on specimen abundance.

- Phase 1 Subset (Head): The eight most abundant families (Cassidae, Conidae, Costellariidae, Cymatiidae, Cypraeidae, Muricidae, Olividae, Volutidae), comprising 390,000 images.

- Phase 2 Subset (Mid-Tier): The next 20 most abundant families (e.g., Strombidae, Pectinidae, Veneridae), selected based on a minimum threshold of 3,000 specimens per family.

All images were resized to 384 x 384 pixels using bicubic interpolation. To prevent data leakage, train-validation splits (90/10) were generated deterministically using a fixed random seed. During training, a "Medium" intensity augmentation pipeline was applied on-the-fly, consisting of random horizontal flips, rotations (+/- 18 degrees), zooms (+/- 10%), and translations (+/- 5%).

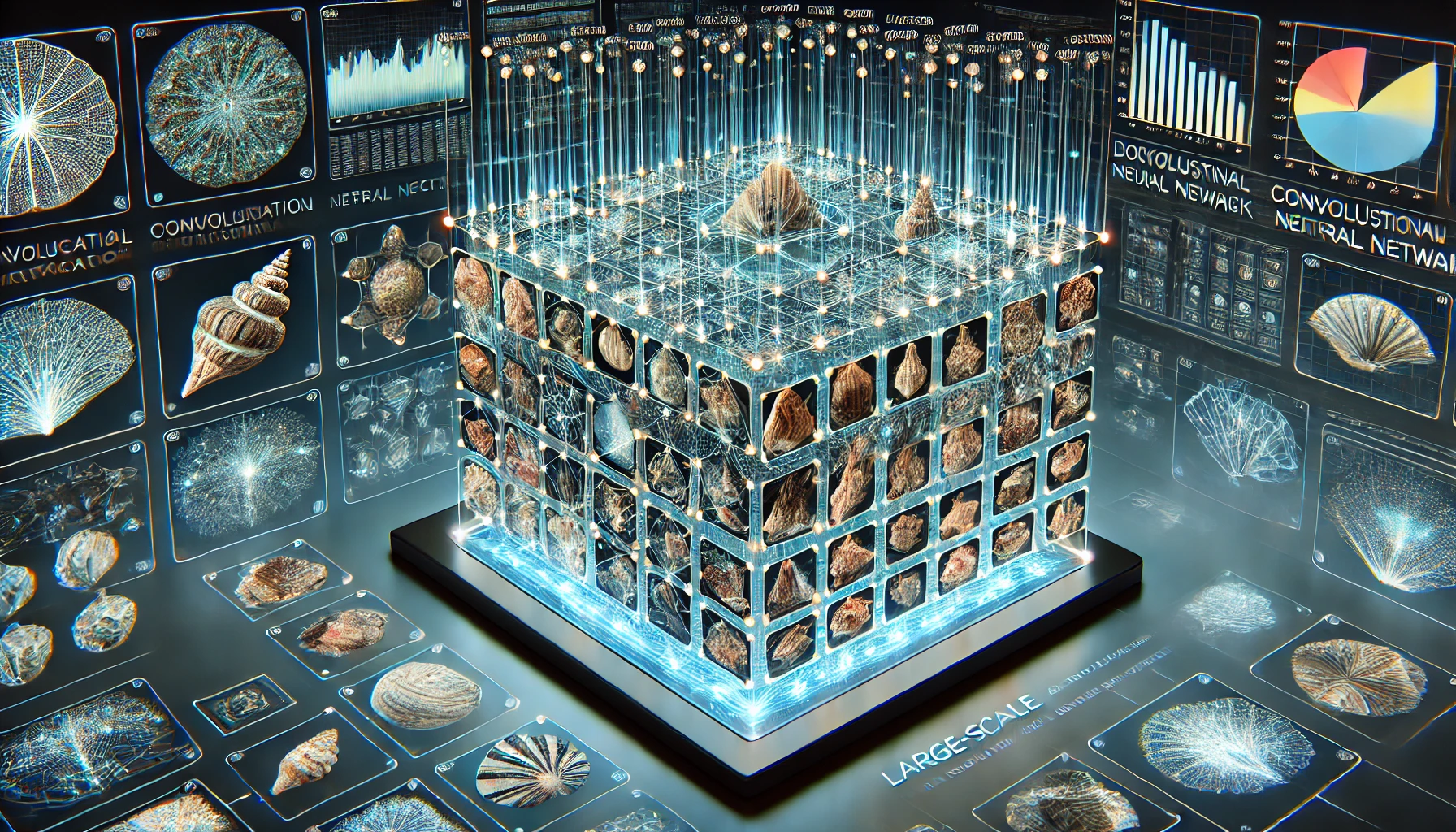

Model Architecture

The backbone utilized was EfficientNetV2-B2 pre-trained on ImageNet. This architecture was selected for its balance of parameter efficiency and high capacity for fine-grained feature extraction. The architecture was modified as follows:

- Feature Extraction: The base network outputs a 1408-dimensional vector.

- Projection Head: A dense bottleneck block was added, consisting of a Dense layer (512 units), Batch Normalization, and Dropout.

- Classification Head: A final Dense layer with Softmax activation, sized according to the number of classes in the active training phase (8 in Step 1; 28 in Step 2).

Training Protocol

Phase 1: Source Domain Initialization

The model was first trained on the eight "Head" families to establish a stable visual baseline. The network was trained end-to-end using the Adam optimizer. To maximize separability in the embedding space, the model was trained until convergence (Validation Accuracy >99%). This state yielded the initial weights theta S1.

Phase 2: Expansion via Rehearsal Learning

To incorporate the 20 mid-tier families without inducing catastrophic forgetting of the original 8, a Rehearsal (Experience Replay) sampling strategy was implemented.

- Data Sampling: A balanced training pipeline was constructed by sampling all available images from the new families (capped at 20,000 per class) and mixing them with a random rehearsal subset of 8,000 images per class from the original "Head" families.

- Head Expansion: The classification layer was replaced with . To accelerate convergence, the weights for the first 8 indices of were initialized with the trained weights from , while the new 20 indices were randomly initialized.

Training in Phase 2 proceeded in two stages:

- Head Warm-up: The backbone and projection layers were frozen. Only the new classification head was trained for 3 epochs (Learning Rate ) to align the new decision boundaries with the existing feature space.

- Partial Fine-Tuning: The top 20% of the backbone layers were unfrozen to allow morphological adaptation to the new classes (e.g., bivalves), while the lower layers remained frozen to preserve low-level texture features. Batch Normalization layers were kept frozen throughout to maintain the source domain statistics. The model was fine-tuned for 8 epochs with a reduced learning rate ( ).

Phase 3: Domain Adaptation via Balanced Head Retraining

To mitigate the performance degradation observed when applying the studio-trained backbone to uncontrolled environments ("in-the-wild" generalization), a targeted domain-adaptation phase was implemented. Unlike the initial backbone training, which relied exclusively on studio images, this phase utilized a fixed feature extractor and focused entirely on optimizing the decision boundary for real-world diversity.

To preserve the high-quality feature representation learned from the 600,000+ studio images, the EfficientNetV2-B2 backbone trained in the previous step was frozen, and the original classification head was replaced with a specialized Cosine Classifier designed to minimize intra-class variance and improve calibration. This new architecture operates in three stages: first, the 1408-dimensional embedding vector is -normalized to lie on a hypersphere; next, a dense layer projects these normalized embeddings onto the 90 family class vectors. Crucially, the weights $W$ are constrained to unit norm with the bias term removed, ensuring that the dot product effectively computes the cosine similarity between the image embedding and the class prototypes. Finally, a learnable temperature scalar is applied to the logits before the Softmax activation ( ) , allowing the network to adapt the "peakedness" of the probability distribution and preventing the under-confidence often associated with raw cosine classifiers.

The training protocol was specifically designed to counter dataset imbalance, particularly where studio images vastly outnumber field and home photographs. To address this, a custom data generator was employed to enforce a minimum domain ratio, ensuring that at least 50% of images in every batch originated from the Field domain. This strategy forces the optimization process to prioritize the most difficult, noisy examples from seashore environments rather than maximizing performance on clean studio data. Furthermore, to encourage linear behavior between classes and improve robustness to outliers, MixUp augmentation was applied with , generating synthetic training examples by taking convex combinations of image pairs and their labels to smooth decision boundaries. Additionally, Label Smoothing was set to 0.05 to prevent the model from becoming over-confident on noisy labels, a common issue in citizen-science data

The head was trained using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of . Training ran for 7 epochs with early stopping based on validation accuracy. To further refine the model's reliability, the final temperature parameter was calibrated to minimize the Expected Calibration Error (ECE), resulting in probabilities that better reflect the true likelihood of correctness.

Implementation Details

All models were implemented using TensorFlow/Keras on a single NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 GPU. Training utilized a batch size of 32 and Sparse Categorical Crossentropy loss. Evaluation metrics included top-1 accuracy, macro-averaged F1-score, and prototype-based nearest-neighbor accuracy using cosine similarity. Reproducibility was ensured by serializing the exact train/validation file splits and class index mappings (labels.json) at every stage.

Results

1. Construction of a Robust Feature Embedding via Progressive Curriculum Learning

To enable domain generalization and open-set recognition in downstream tasks, a robust feature extractor (embedder) was first constructed using a controlled source domain (the studio domain). Rather than training on the full taxonomic hierarchy simultaneously, a two-stage curriculum strategy was employed. This approach prioritized the learning of high-quality visual features from the most abundant families before expanding the morphological scope to mid-tier taxa, thereby stabilizing the backbone against catastrophic forgetting.

1.1 Backbone Initialization on High-Volume Families

The initial feature space was established using the eight most abundant families in the studio dataset (Cassidae, Conidae, Costellariidae, Cymatiidae, Cypraeidae, Muricidae, Olividae, Volutidae). These families account for the vast majority of available training data, with Conidae and Cypraeidae alone contributing over 130,000 images each. An EfficientNetV2-B2 backbone was initialized and trained on this subset using a standard cross-entropy loss.

After capping each class at a maximum of 20 000 images, this resulted in a subset of 145 029 images distributed as follows: 20 000 per class for the four largest families (Cypraeidae, Conidae, Muricidae, Olividae), 19 806 for Costellariidae, 17 088 for Volutidae, 14 854 for Cymatiidae and 13 281 for Cassidae.

The resulting model demonstrated near-perfect convergence on the source (studio) domain. The Step-1 classifier achieved a validation accuracy of 99.6% (Top-1) on a hold-out set of 39,310 images. To validate the quality of the learned representation beyond simple softmax classification, a prototype-based evaluation was conducted using L2-normalized embeddings from the penultimate layer. Nearest-centroid classification on these embeddings yielded a validation accuracy of 98.9%, confirming that the backbone had learned a highly separable metric space for these core families. The confusion matrix for this stage showed negligible inter-class ambiguity, indicating that the intra-family morphological variance was successfully compressed by the encoder. This "Step 1" model served as the weight initialization for the subsequent expansion.

1.2 Feature Space Expansion and Rehearsal

To broaden the morphological coverage of the embedder without diluting the precision achieved on the head families, the model was expanded to include 20 additional "mid-tier" families (e.g., Strombidae, Terebridae, Pectinidae), bringing the total class count to 28. This step introduced significant morphological diversity, adding bivalves (Pectinidae, Veneridae) and limpets (Lottiidae) to a backbone previously dominated by gastropods.

Training was conducted via a rehearsal strategy to mitigate catastrophic forgetting. The training pipeline sampled all available images from the 20 new families (capped at 20,000 per class) while simultaneously sampling a random "rehearsal" subset (8,000 images per class) from the original 8 families. The model head was expanded to 28 outputs, and training proceeded in two phases:

- Head Warm-up: The backbone was frozen, and only the classifier head was trained for 3 epochs. Validation accuracy rose from 81.0% to 96.5% during this phase, indicating that the features learned in Step 1 were already highly transferable to the new families.

- Fine-tuning: The top 20% of the backbone layers were unfrozen (with Batch Normalization layers kept frozen to preserve population statistics). The model was fine-tuned for 8 epochs with a reduced learning rate (1e^-4).

The final Step-2 model achieved a global validation accuracy of 98.8% across all 28 families (23,025 validation images). Crucially, performance on the original 8 "head" families remained robust, with F1-scores remaining above 0.98 for all original classes (e.g., Conidae 0.992, Cypraeidae 0.994), demonstrating that the rehearsal strategy successfully prevented feature erosion.

Table 1: Per-Class Performance of the Expanded Embedder (Selected Families) Evaluation of the Step-2 model on the validation split. The embedding space successfully accommodates distinct morphologies, though minor degradation is observed in visually variable families like Buccinidae.

| Family Group | Family | Support | Precision | Recall | f1 score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head (Original) | Conidae | 800 | 0.986 | 0.998 | 0.992 |

| Cypraeidae | 800 | 0.993 | 0.995 | 0.994 | |

| Muricidae | 800 | 0.981 | 0.988 | 0.984 | |

| Mid-Tier (New) | Strombidae | 1312 | 0.999 | 0.985 | 0.996 |

| Pectinidae | 803 | 0.999 | 0.985 | 0.992 | |

| Buccinidae | 603 | 0.962 | 0.973 | 0.968 | |

| Fasciolariidae | 584 | 0.959 | 0.995 | 0.976 | |

| Global | Overall | 23025 | 0.987 | 0.988 | 0.988 |

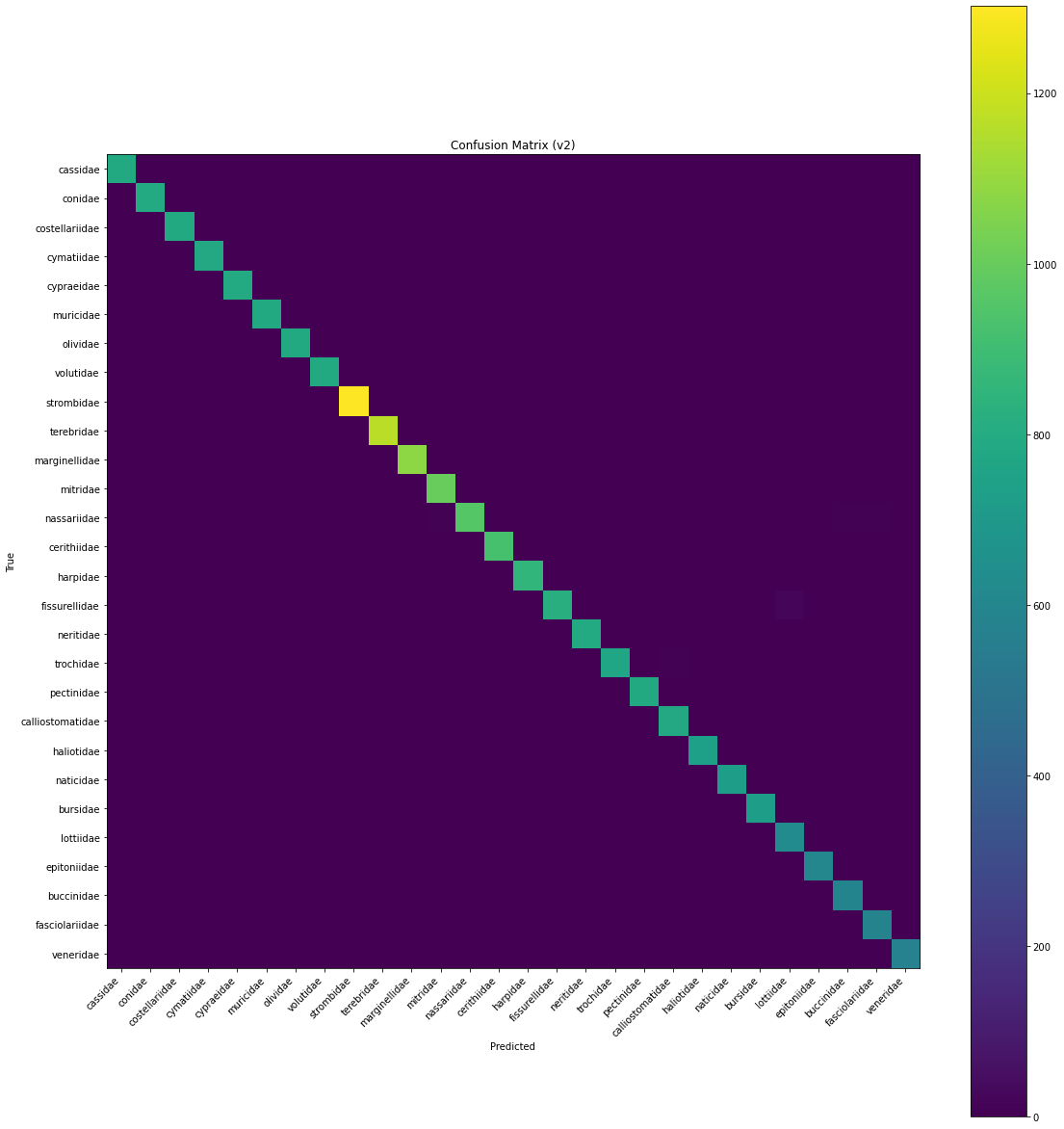

Figure 2: Confusion matrix for 28 families

Analysis of the confusion matrix (Figure 1) reveals that errors are largely confined to morphologically adjacent groups. For instance, the lowest performance was observed in Buccinidae (F1=0.968) and Fasciolariidae (F1=0.976), two families known for high phenotypic plasticity and convergent shell shapes.

The resulting backbone — specifically the output of the penultimate layer prior to the classification head — was exported as the embedding model. This frozen feature extractor projects input images into a 512-dimensional L2-normalized space. This embedder forms the invariant foundation for the domain generalization experiments described in subsequent sections, ensuring that comparisons between Studio, Home, and Field classifiers are based on a shared, high-quality morphological representation.

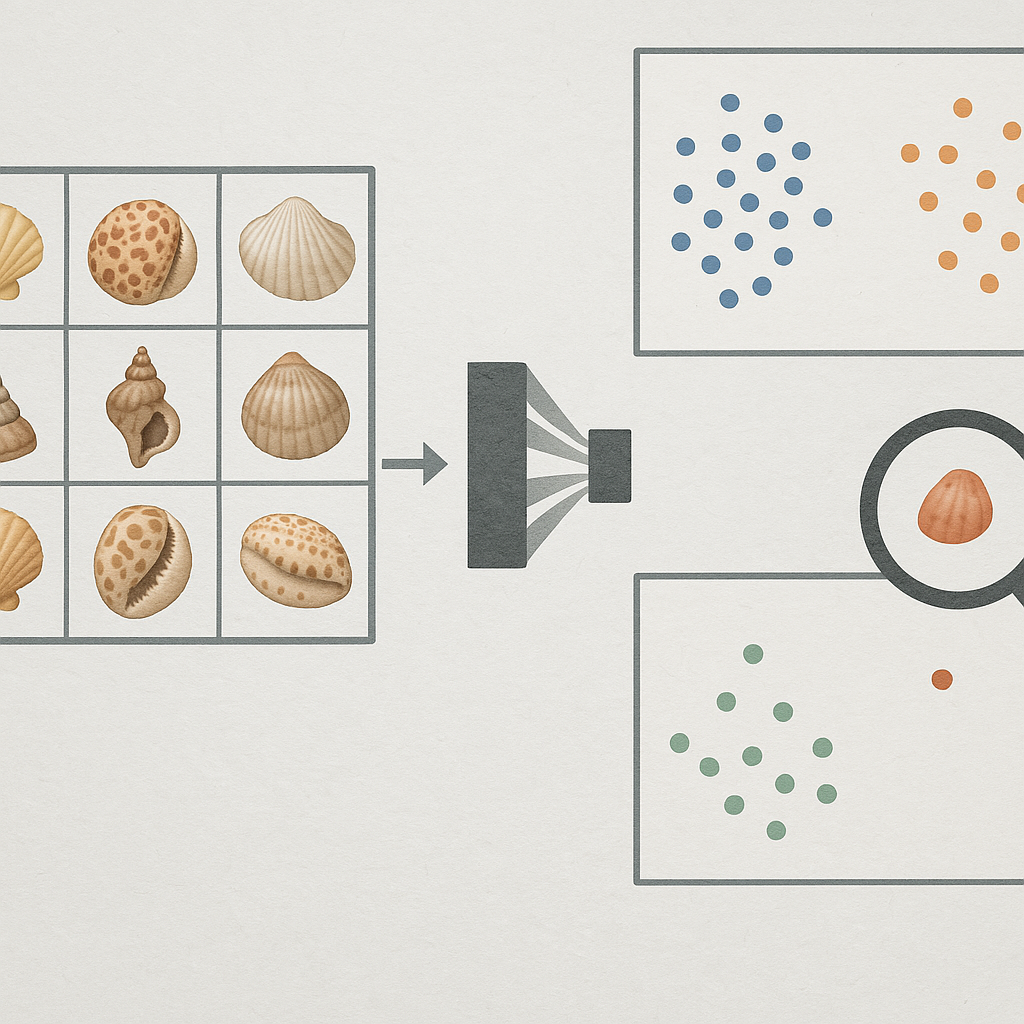

2. Domain-Balanced Head Retraining

To address the substantial performance degradation observed when applying studio-trained models to real-world images ("studio-to-field gap"), the performance of the Domain-Balanced Head Retraining strategy was evaluated. In this phase, the embedding backbone (EfficientNetV2-B2) was frozen, and a new 90-class classification head was trained using a curriculum emphasizing domain diversity (≥50% field images per batch, MixUp augmentation, and label smoothing).

2.1. Global Performance and Generalization

The model demonstrated a significant improvement in global generalization capabilities compared to the baseline model (Model v01, [6]).

- Overall Accuracy: The domain-balanced model achieved an overall accuracy of 0.821 across all domains, representing a +12.6 percentage point (pp) increase over the baseline Model v01 accuracy of 0.695.

- Uncertainty Calibration: A critical improvement was observed in the model's calibration. The global Log Loss decreased from 1.675 (Model v01) to 0.793. This halving of the log loss indicates that the model is not only more accurate but significantly less over-confident in its erroneous predictions, a key requirement for reliable automated species identification systems.

2.2. Domain-Specific Analysis

Breaking down performance by domain reveals the trade-offs inherent in balancing a classifier for "in-the-wild" usage. The primary objective of improving field robustness was successfully achieved; the model yielded a substantial accuracy gain of 13.4% in the Field domain compared to the baseline. This improvement confirms that retraining the head with a heavy weighting on field samples allows the classifier to better map frozen studio-based embeddings to noisy, real-world inputs. Conversely, as expected with domain balancing, a minor regression occurred in the source domain, where Studio accuracy dropped by 4.9%. This specific trade-off implies that the baseline model was likely over-fitting to studio-specific artifacts, such as uniform black backgrounds, while the new model has adopted a more generalized decision boundary. Finally, performance in the Home domain showed a mixed response with an 8.2% decrease in top-1 accuracy. However, the accompanying dramatic reduction in global log loss indicates that although the model may be more conservative in ambiguous settings, its probability estimates have become significantly more reliable.

2.3. Calibration and Reliability

The reduction in Log Loss enables the deployment of confidence-based rejection thresholds. The model halves the uncertainty associated with predictions, allowing for a more effective "reject" mechanism where low-confidence predictions (e.g., max probability $< t$) can be filtered out to maintain high system precision.

| Metric | Model v01 (Baseline) | New Model | Delta |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy | 0.695 | 0.821 | +0.126 |

| Log Loss (Lower is better) | 1.675 | 0.793 | -0.882 |

| Field Accuracy Gain | - | - | +0.134 |

| Studio Accuracy Gain | - | - | -0.049 |

In conclusion, this new model successfully converts the specialized studio embedder into a robust generalist classifier. While a small amount of precision was sacrificed on high-quality studio images, the model gained substantial robustness on field data and achieved a 50% reduction in global uncertainty, making it suitable for deployment in diverse real-world environments.

Discussion

The “Generalization Tax”: Stability–Plasticity Trade-off Across Domains

The most salient outcome of the domain-balanced training strategy is the asymmetric shift in performance across domains: a substantial gain of +13.4 percentage points in the Field domain accompanied by a −4.9 percentage point decrease in Studio accuracy. At first glance, such a reduction on the source domain might appear undesirable. However, this pattern is best understood as a generalization tax—a necessary trade-off between specialization to idealized conditions and robustness under realistic deployment scenarios.

Near-perfect performance on a controlled source domain can mask underlying fragility. Models trained exclusively on studio images may exploit dataset-specific regularities that correlate with class labels but are not intrinsic to the underlying morphological task. These include uniform black backgrounds, consistent lighting conditions, and canonical object centering. When confronted with home or field images—characterized by textured backgrounds, variable illumination, arbitrary viewpoints, and partial occlusions—such shortcuts are unreliable or absent, resulting in substantial performance degradation. This phenomenon is part of a broader category of dataset bias, where learned models encode idiosyncratic correlations present in the training distribution but not in varied real-world settings, leading to sharp drops in accuracy when distributions shift. Prior work has documented that dataset biases can lead to poor generalization when the test distribution diverges from the training distribution, highlighting the importance of addressing distribution shift explicitly [16].

Importantly, this observation does not imply that the studio-trained representation is deficient for its intended purpose. On the contrary, the controlled acquisition conditions of studio images enable the backbone to learn highly discriminative and stable morphological features, which are well suited for family-level classification. The performance degradation observed under domain shift reflects a mismatch at the level of the decision boundary rather than a lack of representational capacity. In this framework, the embedding is treated as an expressive but biased basis, while robustness is enforced through head-level adaptation.

The domain-balanced head retraining strategy directly mitigates this issue by emphasizing exposure to Field conditions during optimization. By substantially increasing the representation of Field images in training batches, the classifier is encouraged to down-weight features that are predictive only under studio conditions and to rely instead on morphological cues that persist across environments, such as global shell shape, aperture geometry, macro-sculpture, and patterning. This re-weighting naturally reduces separability in the pristine studio distribution—where domain-specific cues were maximally informative—but yields markedly improved robustness in real-world contexts. The observed decrease in Studio accuracy should therefore be interpreted not as degradation of inherent representation quality, but as an intentional shift away from brittle domain-specific decision boundaries toward features that generalize more reliably.

This pattern of a performance gap between in-distribution and out-of-distribution evaluation is well established in the machine learning literature. Benchmarks designed to emulate real-world distribution shifts, such as the WILDS suite, show that standard empirical risk minimization produces models that achieve substantially higher performance on in-distribution test data than on shifted test domains, even when various adaptation methods are applied [14]. These results underscore that achieving robustness under realistic shifts often requires deliberate strategies that depart from optimization solely on source domain accuracy.

The trade-off observed here also echoes broader theoretical and empirical findings about the challenges of generalization under shift. While the classical bias–variance trade-off in supervised learning addresses the balance between fitting training data and generalizing to unseen samples, distribution shift introduces an additional dimension: a model may fit the training distribution very well yet exhibit high error when the underlying test distribution changes, because features learned from spurious correlations cease to hold.

Under these conditions, improving worst-case or out-of-distribution performance often entails a deliberate sacrifice of peak in-distribution accuracy, converting specialized decision boundaries into ones that better capture the task-relevant structure of the data.

In the present setting, such a trade-off is not only tolerable but necessary for deployment. Field images represent the most frequent source of uncertainty and failure in practical usage of the IdentifyShell system, and robustness in that domain has a disproportionate impact on overall system utility. A classifier that is marginally less precise under idealized studio conditions but substantially more reliable under field conditions is strictly preferable for biodiversity applications where images are contributed by diverse users in varied environments.

It is important to acknowledge that the generalization tax observed here is not necessarily a fundamental limit. The −4.9 percentage point reduction in Studio accuracy reflects a particular operational choice in domain weighting and optimization strategy rather than an irreducible genetic constraint of the model architecture or features. More explicit multi-objective formulations that balance studio and field objectives simultaneously, or domain-conditional decision boundaries that route inputs to specialized heads based on estimated domain context, could allow recovery of some studio peak performance without compromising field robustness. Nonetheless, the current results demonstrate that deliberately shifting emphasis away from artificial in-domain cues yields a classifier that is far better aligned with the demands of real-world biodiversity imaging.

In summary, the observed stability–plasticity trade-off should be interpreted as evidence that high performance on idealized studio conditions was partially driven by domain-specific regularities rather than robust morphological understanding. Paying a modest generalization tax yields a classifier that is substantively more useful for real-world shell identification tasks, providing a principled foundation for subsequent improvements in calibration, feature invariance, and curriculum strategies aimed at further narrowing domain gaps [15].

Decoupling Feature Learning from Decision Boundaries

The efficacy of the head-only retraining strategy offers critical insight into the nature of the domain gap in molluscan taxonomy: the failure of the baseline model on field images was not due to a lack of representational capacity, but rather a misalignment of the decision boundary. By freezing the EfficientNetV2 backbone—originally trained on 600,000 studio images—and updating only the classification head, we effectively decoupled feature learning from domain adaptation. The resulting +13.4% accuracy gain in the Field domain provides strong empirical evidence that the morphological features learned in the high-quality studio domain (Source) are robust and transferable to the wild (Target), provided the classifier is calibrated to ignore environmental noise.

This finding aligns with recent theoretical work in transfer learning, which suggests that when a model is pre-trained on a high-quality large-scale dataset, full fine-tuning on a smaller, noisier target distribution can actually degrade performance by distorting the pre-trained features [12]. In the context of Single Domain Generalization (SDG), attempting to fine-tune the entire network on a limited set of variable field images would likely have caused the backbone to "forget" the subtle, invariant structures of shell sculpture in favor of easier, spurious correlations present in the seashore environments (e.g., sand texture or water reflection). This phenomenon has been formalized in recent studies showing that "last-layer retraining" is often sufficient to mitigate reliance on spurious background features without altering the underlying encoder [13].

By strictly enforcing a frozen backbone, the new model was forced to utilize the existing "studio" feature space—a space where families are already well-separated based on intrinsic morphology—and simply learn a new linear mapping that is robust to the artifacts of outdoor photography. This validates the utility of museum and studio collections as the primary engine for training biodiversity models. It demonstrates that expensive, difficult-to-acquire "in-the-wild" data is not necessarily required to learn the fundamental visual dictionary of a phylum, but is instead best utilized to calibrate the final decision logic [11]. Consequently, the "studio-to-field" gap in automated identification can be bridged not by discarding museum data, but by treating it as a stable foundation for feature extraction, independent of the deployment environment.

The effectiveness of head-only retraining indicates that the degradation observed under domain shift did not primarily originate from deficiencies in the learned feature representation. Instead, the failure of the baseline model in home and field settings reflects a misalignment at the level of the decision boundary. The studio-trained backbone was already capable of encoding discriminative morphological information, as evidenced by its near-perfect in-domain performance and strong prototype separability. However, when deployed under unconstrained imaging conditions, the original classification head assigned excessive weight to unstable cues correlated with the studio acquisition process, resulting in brittle predictions. The substantial recovery in field accuracy achieved without modifying the backbone therefore supports the interpretation that domain generalization in this setting is fundamentally a boundary reweighting problem rather than a representational capacity problem.

Freezing the backbone during domain adaptation is not merely a conservative choice but a strategically advantageous one. The backbone was trained on more than 600,000 high-quality studio images, allowing it to learn fine-grained morphological features with high signal-to-noise ratio. Fine-tuning such a representation on comparatively small and noisy field datasets risks eroding globally useful features and overfitting to spurious correlations specific to particular environments, such as sand texture, lighting artifacts, or background clutter. By contrast, freezing the backbone preserves the integrity of morphology-centric features while allowing the classifier head to selectively down-weight unstable dimensions exposed by domain diversity. This separation prevents representational drift while still enabling substantial robustness gains.

This behavior is consistent with a growing body of transfer-learning literature demonstrating that strong pretrained representations often generalize best when adaptation is restricted to shallow classifiers. Studies across natural and medical image domains have shown that retraining only the final layers — or applying linear probes — can outperform full fine-tuning under distribution shift, particularly when target-domain data are limited or noisy [20]. In such settings, updating all network parameters can distort otherwise robust features, whereas head-only retraining effectively reinterprets a fixed embedding space without collapsing it. The present results extend these findings to fine-grained biological classification, showing that a studio-trained backbone can serve as a stable substrate for domain adaptation when combined with appropriate decision-level learning [13].

It is important to distinguish the role of the frozen backbone in the present classification framework from its suitability for morphological interpretation. In this work, the backbone is treated as an expressive but potentially biased feature basis, optimized for discriminative performance rather than for disentangling intrinsic morphological variation from acquisition effects. While head-only adaptation is sufficient—and empirically effective—for improving classification robustness, it does not render the embedding itself domain-invariant. Consequently, although the frozen backbone is well suited for operational family-level classification, analyses that rely on embedding geometry as a proxy for phenotypic similarity, such as morphological variability studies or species delimitation, require separate representations explicitly regularized for domain invariance.

More broadly, these findings highlight the value of decoupling representation learning from decision-boundary optimization in biodiversity informatics. Large, curated museum or studio collections remain highly effective for learning rich visual representations, even when deployment data originate from uncontrolled environments. Rather than discarding such resources or attempting to retrain representations on sparse field data, substantial robustness gains can be achieved by treating domain generalization as a decision-level problem. This perspective is particularly relevant for taxonomic applications, where high-quality labeled data are abundant in controlled settings but scarce in the wild.

The Importance of Calibration over Raw Accuracy

While accuracy remains a common headline metric in image classification, it provides an incomplete picture of model reliability under real-world conditions. This limitation is particularly acute in citizen-science and biodiversity applications, where incorrect predictions may propagate downstream errors or mislead users. In this context, the substantial reduction in Log Loss observed in the domain-balanced model (from 1.675 to 0.793) represents one of the most practically significant outcomes of this study, even in domains where top-1 accuracy did not improve uniformly.

Log Loss captures not only whether predictions are correct, but how well predicted probabilities align with empirical correctness [18]. High Log Loss values indicate overconfident misclassifications — a failure mode that is especially problematic in hierarchical taxonomic pipelines, where early-stage errors preclude recovery at later genus- or species-level classifiers. The baseline studio-trained model exhibited precisely this behavior: confident predictions on field images that were frequently incorrect, reflecting reliance on brittle domain-specific cues. By contrast, the domain-balanced head produced probability estimates that were markedly better calibrated, as evidenced by the near halving of Log Loss.

This improvement can be attributed to several interacting design choices. First, the cosine classifier constrains both feature embeddings and class prototypes to lie on a hypersphere, reducing uncontrolled logit growth and encouraging angular separation rather than magnitude-based confidence inflation. Second, label smoothing explicitly penalizes extreme probability assignments, mitigating the tendency of deep networks to become overconfident on noisy or ambiguous samples [19]. Third, MixUp augmentation further smooths decision boundaries by enforcing linear behavior between classes, a property known to improve both robustness and calibration under distribution shift. Together, these mechanisms bias the classifier toward cautious correctness rather than aggressive specialization.

Importantly, the calibration gains persist even in domains where raw accuracy declined, such as the Home setting. This apparent paradox underscores a critical distinction: a model that is less accurate but appropriately uncertain can be more useful than a model that is marginally more accurate but confidently wrong [17]. In practical deployment, calibrated uncertainty enables the implementation of confidence-based rejection thresholds, allowing the system to abstain when predictions fall below a reliability threshold. This transforms the classifier from a forced-decision system into a selective predictor capable of deferring ambiguous cases for human review or downstream processing.

The emphasis on calibration aligns with a growing body of evidence that modern deep networks are systematically miscalibrated, particularly under distribution shift. Prior studies have shown that models trained with standard cross-entropy objectives tend to produce overconfident predictions, and that this effect worsens when test data deviate from the training distribution. Temperature scaling and related post-hoc calibration techniques can partially address this issue, but architectural and training-level interventions — such as cosine classifiers, label smoothing, and data mixing — are increasingly recognized as more robust solutions.

In the context of IdentifyShell and similar biodiversity platforms, calibrated confidence is not merely a secondary metric but a core requirement for responsible deployment. Reliable uncertainty estimates enable safer user feedback, reduce the risk of propagating incorrect labels through hierarchical classifiers, and provide a principled signal for active learning and dataset expansion. From this perspective, the observed reduction in Log Loss represents a qualitative shift in model behavior: the classifier transitions from an overconfident studio specialist to a cautious generalist better suited for real-world ecological data.

Curriculum Learning and Domain-Balanced Training as an Implicit Robustness Mechanism

The success of the domain-generalized classifier cannot be attributed solely to architectural choices at the head level, but also to the way training data were presented during optimization. In particular, the deliberate enforcement of a minimum proportion of Field images in every batch represents a form of curriculum learning that prioritizes robustness over convenience [21]. Under the natural data distribution, studio images vastly outnumber home and field photographs. Standard uniform or proportional sampling would therefore bias gradient updates toward the clean, high-signal studio domain, effectively marginalizing the very conditions under which the model is most likely to fail at deployment.

By enforcing a ≥50% Field ratio per batch, the optimization process is compelled to focus on the most challenging samples throughout training. This strategy prevents the classifier from converging to decision boundaries that perform well on the dominant source domain but generalize poorly elsewhere. Instead, gradients are repeatedly shaped by images exhibiting background clutter, variable lighting, partial occlusion, and non-canonical viewpoints. In effect, the model is trained under a “worst-case” curriculum, where robustness to uncontrolled environments becomes a primary objective rather than a secondary by-product.

This approach aligns with broader findings in curriculum and data-centric learning, which show that the order and composition of training samples can be as influential as model architecture in determining generalization behavior. Presenting harder or more diverse examples early and consistently during training has been shown to encourage the learning of more invariant representations and decision rules. In the present case, domain balancing functions as a curriculum over acquisition conditions rather than over class difficulty, ensuring that invariance to environmental variation is learned explicitly rather than assumed.

The effectiveness of this strategy is further amplified by the interaction with MixUp augmentation and label smoothing. MixUp encourages linear behavior between classes by constructing convex combinations of inputs and labels, thereby discouraging sharp, brittle decision boundaries that hinge on spurious cues. When applied in conjunction with domain-balanced sampling, MixUp forces the classifier to interpolate between morphologically similar shells across heterogeneous backgrounds and lighting conditions, smoothing transitions in embedding space that would otherwise be fragmented by domain artifacts [22]. Label smoothing complements this effect by penalizing extreme confidence assignments, reducing the incentive to overfit noisy or ambiguous field samples [19].

Importantly, these mechanisms operate primarily at the level of optimization geometry rather than representation learning. The frozen backbone provides a fixed feature space, while domain-balanced sampling, MixUp, and label smoothing collectively shape how that space is partitioned. This separation explains why substantial robustness gains can be achieved without modifying the feature extractor: the curriculum alters which dimensions are emphasized during learning, not which dimensions exist. In this sense, the training strategy functions as an implicit regularizer that biases the classifier toward domain-stable cues without requiring explicit domain adversarial losses or multi-domain backbone training [13].

From a practical perspective, this finding underscores the importance of data presentation strategies in biodiversity informatics, where domain imbalance is the norm rather than the exception. Field data are often scarce, noisy, and heterogeneous, yet they dominate real-world usage. Treating such data as first-class citizens during training—rather than as a small perturbation to a clean source distribution—can yield disproportionate gains in robustness. The present results demonstrate that carefully designed curricula can partially substitute for more complex domain generalization machinery, offering a simple and scalable path toward reliable performance in unconstrained environments.

Conclusion

In summary, this study demonstrates that robust family-level shell classification under domain shift can be achieved without retraining the feature extractor, by treating domain generalization as a decision-boundary and training-dynamics problem rather than a representational one. By combining a high-capacity studio-trained backbone with domain-balanced head retraining, calibrated outputs, and curriculum-aware optimization, substantial gains in real-world robustness were obtained while preserving compatibility with hierarchical taxonomic pipelines. These findings establish a practical and reproducible baseline for molluscan image classification and provide a foundation for future work on domain-aware routing, open-set recognition, and morphology-driven species delimitation.

References

- [1] Rosa RM, Cavallari DC, Salvador RB iNaturalist as a tool in the study of tropical molluscs PLoS ONE 17(5): e0268048. (2022)

- [2] G Van Horn et al. The iNaturalist Species Classification and Detection Dataset arXiv:1707.06642 [cs.CV] (2017)

- [3] K Newcomer et al. Evaluating Performance of Photographs for Marine Citizen Science Applications Front. Mar. Sci., Volume 6 (2019)

- [4] Wäldchen & Mäder Plant species identification using computer vision techniques Ecological Informatics, Volume 40, Pages 104–122. (2018)

- [5] Ph. Kerremans. Hierarchical CNN to identify Mollusca. IdentifyShell.org (2025)

- [6] Ph. Kerremans. Optimizing Molluscan CNN Taxonomy: Balancing Hierarchy Simplification, Data Volume, and Augmentation for Improved Classification. IdentifyShell.org (2025).

- [7] PW Koh et al. WILDS: A Benchmark of in-the-Wild Distribution Shifts. arXiv:2012.07421 [cs.LG] (2020).

- [8] R Taori et al. Measuring Robustness to Natural Distribution Shifts in Image Classification. arXiv:2007.00644 [cs.LG] (2020).

- [9] I Gulrajani & D Lopez-Paz In Search of Lost Domain Generalization. arXiv:2007.01434 [cs.LG] (2020).

- [10] F Qiao, L Zhao, X Peng Learning to Learn Single Domain Generalization. arXiv:2003.13216 [cs.CV] (2020).

- [11] S Kornblith, J Shlens, Quoc V. Le Do Better ImageNet Models Transfer Better?. arXiv:1805.08974 [cs.CV] (2019).

- [12] A Kumar et al. Fine-Tuning can Distort Pretrained Features and Underperform Out-of-Distribution. arXiv:2202.10054 [cs.LG] (2022).

- [13] P. Kirichenko, P. Izmailov, and A. G. Wilson. Last Layer Re-Training is Sufficient for Robustness to Spurious Correlations. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) (2022)

- [14] Koh, P. W. et al. WILDS: A Benchmark of in-the-Wild Distribution Shifts. ICML (2021)

- [15] Zhang, H. et al. Theoretically Principled Trade-off between Robustness and Accuracy. ICML (2019)

- [16] Torralba, A., & Efros, A. A. Unbiased Look at Dataset Bias. CVPR (2011)

- [17] Guo, C. et al. On Calibration of Modern Neural Networks. ICML (2017)

- [18] Hendrycks, D. & Gimpel, K. A Baseline for Detecting Misclassified and Out-of-Distribution Examples ICLR (2017)

- [19] Müller, R., Kornblith, S., & Hinton, G. When Does Label Smoothing Help? NeurIPS (2019)

- [20] Raghu et al. Transfusion: Understanding Transfer Learning for Medical Imaging NeurIPS (2019)

- [21] Bengio, Y. et al. Curriculum Learning. ICML (2009)

- [22] Zhang, H. et al. mixup: Beyond Empirical Risk Minimization ICLR (2018).